Unsettled Landscapes: An Interview with Andrea Bowers

Published on ArtSlant

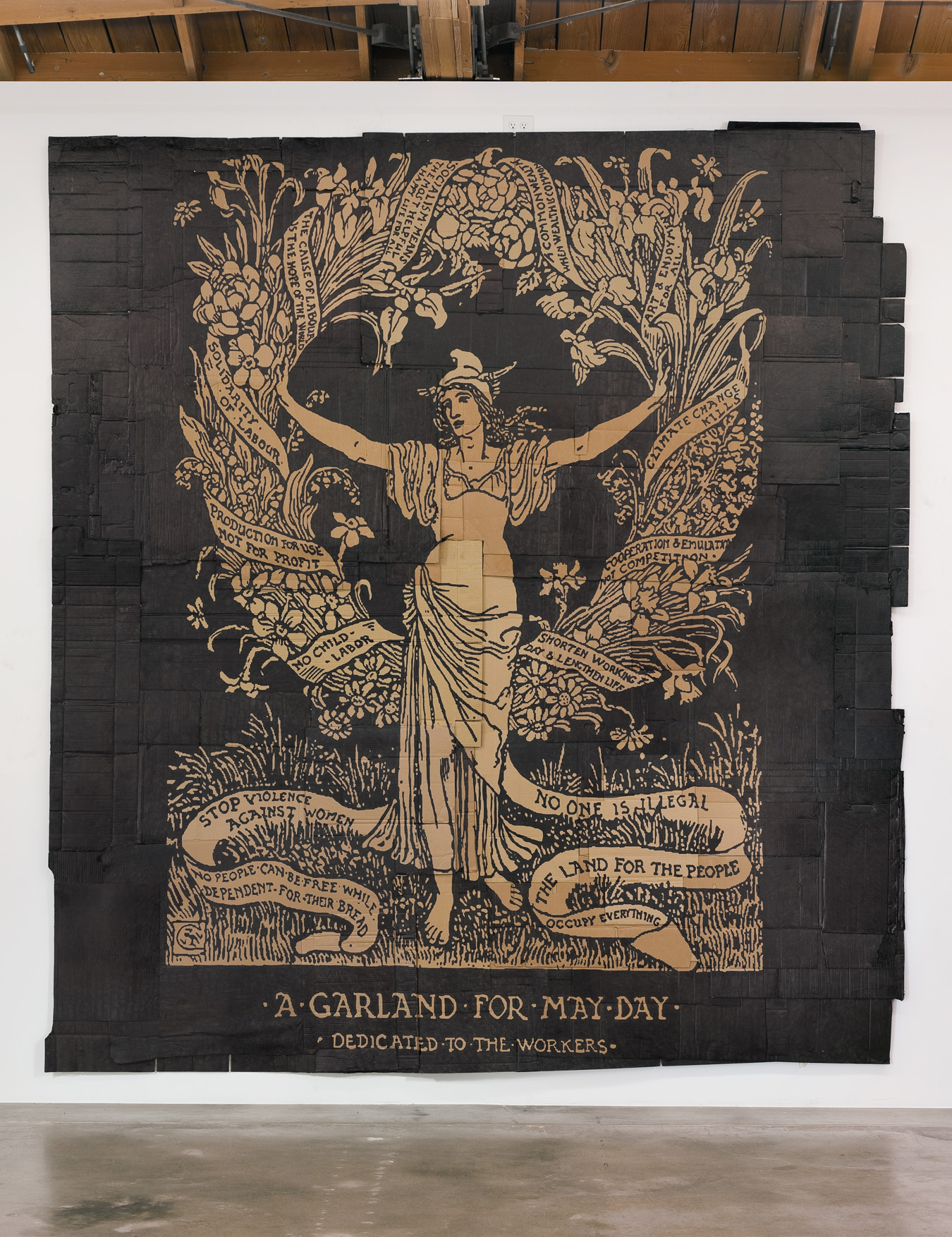

Andrea Bowers, A Garland for May Day (Illustration by Walter Crane), 2012, Marker on found cardboard, 156" H x 140" W (396.24 cm H x 355.6 cm W), Gallery Inventory #BOW353; Courtesy of Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects; Photo: Robert Wedemeyer

Santa Fe, Jul. 2014: Landscapes are solid, material, and stable masses. They are both a format of image and a type of content within an image that we register with familiarity, easily recognizable by the divisible line that categorizes land from sea, and terrain from sky. One part is always more ethereal than the other. The distinctive, and more concrete elements are part of our tangible purview, things we interact with, can touch. The formula of a landscape is a binary that depends on a complex foreground against a more atmospheric backdrop. The horizon line is essential in defining the term landscape. But what happens when we can view the horizon all too clearly?

Andrea Bowers is an artist whose practice is formed through advocacy. Her most recent exhibition, Unsettled Landscapes, which opened this past week at SITE Santa Fe, includes two new works that fit perfectly into the title of this year’s biennial. Bowers’ work registers on both platforms of the term unsettled—unstable and unoccupied—in her piece Memorial to Arcadia Woodlands Clear-Cut (Green, Violet, Brown), and The United States v. Tim DeChristopher. Both works mark new methods of disrupting or displacing the materials we justify as belonging to landscape—namely the foreground itself. She takes protests of clearcutting woods and the civil disobedience surrounding land auctions to create sculptures and films that approach a more intimate relationship with aspects that are absent, and willfully destroyed. Bowers moves toward a more fluid understanding of, and perhaps tragically more minimal, definition of land.

Stephanie Cristello: Perhaps it is best to start with considering how your work more generally subsets within the conceptual framework of Unsettled Landscapes. Your work in particular registers with this notion of unrest—would you say activism in art plays a role of “unsettling the landscape” all its own?

Andrea Bowers: Yes—my works in SITElines investigate the role that humans play in directly unsettling the landscape. Particularly, my artworks in this exhibition are documents from the activists who try to actively prevent human intervention onto specific landscapes. The works on view focus on contentious locations where governments and corporations are willing to cause environmental degradation or human rights violations for the purpose of attaining or maintaining power. I am exhibiting two different works that use two different sites in the American West as their subject: both public land in the state of Utah, and clearcut woodlands in Los Angeles County.

SC: In Memorial to Arcadia Woodlands Clear-Cut (Green, Violet, Brown), the work you created specifically for SITE, protest and its documentation become one; the discarded material, or maybe a better word is residue, from the event becomes the material of the work itself. Where does the material of the event end and the artwork begin? Or are they one and the same?

AB: I make formal and material decisions that are inherent within the subject matter—meaning that I do not usually apply external materials. In this way, every subject—or you could say every case—has a unique set of material, formal, and aesthetic qualities that inspire the production of artworks. Two versions of this sculpture exist. The companion piece was first shown as part of Cultivating the Courage to Sin, a project about climate justice and feminist subjectivity in art and activism. It especially focused on a non-violent act of civil disobedience that I was involved in. I was arrested, along with three other activists, for climbing into the trees of a native oak woodland habitat in Arcadia, California, and trying to save a pristine forest of 250 trees from being clearcut by the county of Los Angeles. One of the most horrible and unanticipated outcomes of this action was that all of the trees were ripped out of the forest around us as we were tied to the canopies of two oaks. All of the destroyed trees were then put in wood chippers. Ultimately I was arrested on three misdemeanor charges and placed in jail for two days. Memorial to Arcadia Woodlands Clear-Cut (Green, Violet, Brown) is a large hanging sculpture made from the ropes and materials commonly used by tree sitters. Immediately upon my release from jail, I returned to the site of the clearcut—mountains of wood chips were all that remained from the once majestic trees. It was intellectually and emotionally devastating for me to witness this. I decided to save as many of the wood chips as possible. I filled up a pick up truck with the wood before I was served with a restraining order to stay off the land.

SC: Is Memorial to Arcadia Woodlands Clear-Cut (Green, Violet, Brown) the first time you have been arrested during a piece? How did the restriction from the land affect you?

AB: Yes, that action was the first time I was arrested. It wasn’t really too hard to be restricted from the land because it was so brutal to see. The woodlands had been destroyed by the clearcut, and the landscape had become nothing more than a barren dirt patch.

SC: Can you speak a bit about the metaphor of the tree itself? How does the piece operate on a more formal, even iconographic level?

AB: I don’t think of this work as metaphoric. Perhaps it is closer to metonymy. The wood chips are part of the whole of the original tree. I knew I wanted to attempt to memorialize all of the destroyed trees, as well as find a sculptural way to re-monumentalize them, even if as a representation. Bundles of the wood chips hang at the bottom of the sculpture, using the formal quality of gravity to speak to the weight of the subject matter in a way. The 250 pristine old growth trees were ripped out of the woodlands so that the area could be turned into a dumping ground for dirt and debris scraped from the bottoms of the concrete L.A. river network. In this piece, aesthetics and pathos are used to create a conversation surrounding the crucial need to protect our last areas of urban wilderness.

SC: The protest that provides the material basis of this work was in 2011. How does time change the impact of the event on both you and your work? Time does not necessarily create distance—do you find you come closer to distilling the event by re-experiencing it for the purposes of making a piece?

AB: Over time, I continue recording and participating in activist campaigns and actions that speak to issues that I am passionate about. I hope that before I leave this planet I have created a body of work that is in service to the issues of social justice, gender equality, workers rights, and climate justice. I hope that I will develop a body of work that bears witness to and pays homage to the powerful activists that have fought for these causes, and it is my aim that perhaps my work can serve as a kind of historical record of these under-told stories.

The other work included in the exhibition pays tribute to a similar but different act of civil disobedience. The United States v. Tim DeChristopher is a new single channel video focusing on a Utah student who, posing as a bidder, disrupted a government auction of 150,000 acres of wilderness for oil and gas drilling. In December of 2008, Tim DeChristopher bid on and won fourteen parcels (22,000 acres) of land near Arches National Park and Labyrinth Canyon worth $1.8 million—only to then announce that he had neither the intention, nor the money to pay for them. Once authorities realized what DeChristopher was doing, the auction was stopped and he was arrested. Many of the leases, which would have permitted drilling on pristine acres of public land in Utah, including some of America's most beautiful and environmentally sensitive red-rock desert, were subsequently canceled. DeChristopher spent two years in jail for this action. The video includes an interview with him, as well as footage of me walking through the gorgeous land in Utah that Tim saved. His actions to protect the landscape from becoming unsettled were heroic.

SC: Life and art do not appear to have much of a distinction for you, perhaps more so than for other artists.

AB: My practice is a form of advocacy.

SC: In this vein, how important is it that your viewers are fully aware of the political and event-based implications of your work when experiencing the piece? Some of your references are very direct, but others are more nuanced.

AB: I don’t separate the aesthetic experience from politics. I don’t think it is possible. It is crucially important that people are aware of the political content of my work when experiencing it.

––