Retrogarde: The Threshold of History

Published on ArtSlant

In the initial stages of writing this piece, I penned a question: What is the threshold of history? It was the morning of November 9, 2016. The question concerned the boundary of public memory. The limit of how this memory is transformed into action. It was a question posed on a precipice, in both popular definitions of the term—between falling off the brink of one territory, and the inception of a new space. That was on November 9. A question about temporary suspension, the moment before one thing becomes the next. I think these qualities are obvious, but write them down anyway.

Rollercoasters, hang time, being neutral.

Politics has no memory.

That was on November 9, a Wednesday. I was thinking about the avant-garde in advance of visiting an exhibition curated by Yesomi Umolu at the Logan Center for the Arts on the University of Chicago campus. Its title is Retrogarde. I think about how I had read it wrongly from the press release weeks before, uttering instead “Retrograde,” and how this realization changes things. I think about the potentials of the correct title, and if they are even possible. I am uncertain yet hopeful. I think about how this sentiment of uncertainty is used in politics as rhetoric in place of feeling, and dislike the opacity of its purpose, but leave it in the piece anyway. To slip and utter “Retrograde” would indeed undo the delicate fabric woven of Umolu’s concept—a movement that seeks not to cycle backward from a fixed position, but rather identify forward-looking ideas within the history of art, the avant-garde, to see how they might be adapted. I come to this conclusion on November 12 after I have seen the exhibition.

The politics of everyday life have inherently changed.

November 12. When I begin to feel bitter I write: this is exactly where the avant-garde belongs. I remove it from the piece. Then I write: this exhibition could not have been more timely.

The six artists on view in Retrogarde — whether in their practice as a whole, or the work on view — stake the relevance, if not necessity, of unearthing how once unconventional practices might still prove useful in the echo chamber of contemporary art. I question how the archive of the avant-garde can maintain the masquerade of noncompliance within a contemporary context—its histories and strategies having been absorbed into the complicit necessity of a counter force within a capitalist structure. Disobedience is normalized. Among the natural and inevitable co-option of avant-garde traditions over the twentieth century, the packaging of the artists’ work within the exhibition takes on the institutional form of the precise object its source material once criticized. Housed within the galleries on the University of Chicago’s campus, the work adheres to the standard conventions of an institutional encounter with contemporary art: expected, customary, routine. This is exactly where the avant-garde belongs. This exhibition could not have been more timely.

The avant-garde exists only in resistance to something else; this is its political edge. Although, defiance is not the platform Retrogarde advances or innovates. Instead, the exhibition reimagines how the avant-garde has acted as a lineage and art historical source to contemporary practice. Despite the radical content of the works’ sources, Umolu does not upend the conventional systems of display or dissemination in favor of rebellion, or even propose that the work included within the exhibition is inherently political, so much as it is politicized through its relationship to current events. Something is still left unsaid.

Samson Kambalu, Nyau Cinema (Hysteresis), Installation view in All the World’s Futures, 56th Venice Biennale, 2015

Samson Kambalu is a Malawi-born, London-based artist and author. In Field Work (2016), short, sepia-hued silent films play on a loop, each reel separated by a text slide describing the singularly repetitive action on view. Belonging to the Nyau Cinema series, which I first encountered in Okwui Enwezor’s All the World’s Futures at the 2015 Venice Biennale, text installed on the wall in both instances defines the films’ terms in ten succinct rules: number 3 states there must always be a conversation between performance and the medium of film; number 6 qualifies acting must be subtle but otherworldly, transgressive, and playful. The film performs itself under every guise of early European cinema, but the footage betrays this appearance. Its anachronism emerges: in Nude Ascending a Staircase (2016), a black man without clothes, save for tube socks and sneakers, runs up a domestic wooden staircase, disappearing out of view after turning on the landing, only to start from the bottom again. A figure trapped in endless ascension. In He Walked on Water (2016), the film splices the artist jumping to capture the figure solely with his feet at the same level of, or higher than, the water—hovering above the sea, frenetically and tenuously balanced on its surface. A similar infinity. How quickly the brevity of repetition reaches the feeling of forever.

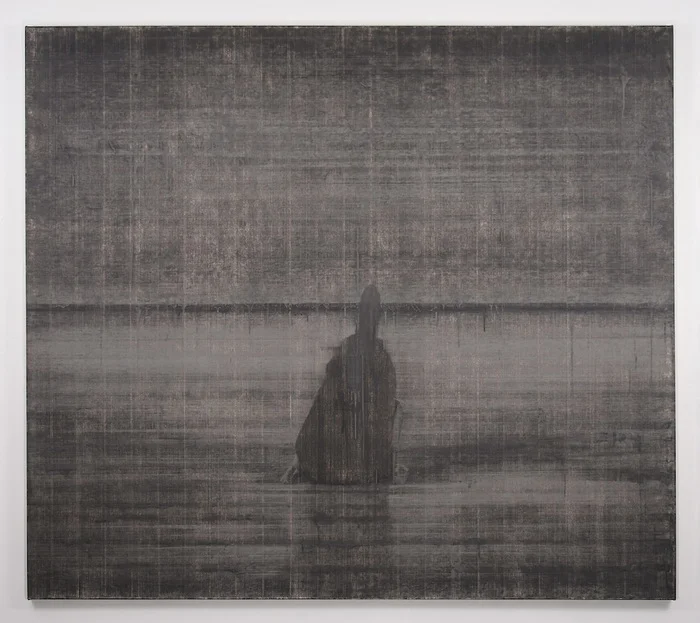

Matthew Metzger, Collapse, Movement 1, 2014. Image courtesy of Arratia Beer, Berlin and Regards, Chicago

In Matthew Metzger’s Collapse, Movement 2 and Collapse, Movement 3 (2016), two nearly identical paintings hang opposite one another, as if mirrored. The image, which is brushed in quickly, yet photo-representational, is rendered from a still in Yvonne Rainer’s seminal 1966 performance Trio A—lifted from one minor second (approx. 2:42) where Rainer is caught mid turn, staring at the sky amid the uninterrupted motions, routines, and gestures that comprise the film. Her back is on the floor, her legs are placed one above the other outstretched, her hands lax by her side, fingers curled, the floor spans out like the horizon of a sea. She floats heavily.

The threshold of history is a film spread thinly across a chronological archive. Beneath the surface, events across time and space rearrange themselves, rising to the top or sinking down, as their philosophical relevance becomes ripe for use as source material.

Throughout Trio A, climax is replaced by continuity. This concept of a continuous gesture—stretching an ideological position into an aesthetic possibility for new work—is in many ways the language of this exhibition, especially in regard to performance. Catherine Sullivan’s ‘Tis Pity She’s a Fluxus Whore (2003) restages actions done for the Festival of New Art (Technical Academy, Aachen, Germany, July 20 1964) where the gathering of twelve artists—including Joseph Beuys, Robert Filliou, and Wolf Vostell—were met with hostile reception by the audience for the political/unconventional content of the acts. The two-channel video features actors executing the original performances, but is foiled through the direction of the film, shot in the style of a seventeenth-century Jacobean drama. Sullivan’s practice emerges as a hybrid of performance and cinema; her interaction with the avant-garde is two-fold—first, of course, in the sampling of Fluxus content, but second, in marrying the dominant and marginal methods of viewing performance itself: video art and theater.

The two channels unfold in near synchronicity, side by side. The voiceover combines texts from the original John Ford play, ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore (1633), with narrative cues from the 1964 actions. In one scene, a recreation of what appears to be a series of circumstances by French artist Robert Filliou, the narrator states in succession:

To address us in a manner of imitating Hitler, Stalin, and Mussolini requires too much intellectual agility.

The comparison of the nude pictorial with a battle plan requires too much intellectual agility.

This extreme polarity between the obvious and the enigmatic requires too much intellectual agility.

Paint flowing from boxes colored like the French flag is messy and requires too much intellectual agility.

At this last statement, the actor in both channels walks along large boxes placed on the stage—blue, red, white—and tilts the boxes, one by one, so that the hole in each pours the colored liquid onto his hand. The red, white, and blue paint swirls, dripping onto the floor, mixing in his palm: the French flag. The temporary suspension before one object transforms into the next. At this precise moment, the efficacy of the avant-garde slipped through the divide between past and present, unbound by time.

This was on November 12 (which was after November 9) and no one in the film spoke about an American flag. The chance calculation of these three colors in action, each contaminating the next, set off the unrehearsed trigger of pathetic fallacy, which rose quite easily to the surface on the threshold of history. While disobedience may be normalized, it is still severely present.

(Image at top: Catherine Sullivan, ’Tis Pity She's a Fluxus Whore, 2003. Image courtesy the artist and Galerie Catherine Bastide)