The Death of Conceptualism: Christopher Williams and The Great Sorting

Published on ArtSlant

Christopher Williams, Bouquet for Bas Jan Ader and Christopher D’Arcangelo, 1991; Lorrin and Deane Wong Family Trust, Los Angeles / © Christopher Williams / Courtesy of the artist; David Zwirner, New York/London; and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne.

A single image in an empty room. The signature contrast of seventeenth-century Dutch-still life permeates the pictorial field, Easter lilies occupying a significant quotient of the bouquet, delicate white crespias folded between the rich green of the leaves laid flat against the soft, white tablecloth, patterned only by the table visible through the opacity of the thinly woven fabric. The background in the distance is a pitch black, the kind that could only exist in a photo studio; the image is sharp, close, and clear; a barely noticeable soft focus blurs the edge of the table, a softened horizon line. This singular image is placed just to the left of the exit of an otherwise vacant gallery. It is positioned for the departing—available for viewing only after the visitor has traversed the length of the gallery, making their way out. Once you meet this image, there is nothing to see behind you, no reason to turn back, un-beholden to the space. The image of this particular bouquet is the only experience you will find in this room, the single reason you entered, and the only reason you will reflect back on the experience of the room once you have left it. The image openly deserts you, yet does not allow you to abandon it. It is neither haunting nor serene, neither sweet nor elegiac—cold and stark, though not without sentiment. The image in question, Bouquet for Bas Jan Ader and Christopher D’Arcangelo, is one of three viewing experiences we are handed in the current retrospective Christopher Williams: The Production Line of Happiness, on view at the Art Institute of Chicago.

The piece is a direct allusion, a nominal mention of two dead conceptualists. D’Arcangelo, known for his anti-institutional contributions in the early 1970s, committed suicide in 1979 at age twenty-four while working on a proposal for the museum of contemporary art in Eindhoven, Netherlands; Ader was lost at sea during in an unfinished performance of his piece In Search of the Miraculous, presumed dead since 1975 at age thirty-three. Other than the brevity of their careers, the two artists chosen for the namesake by Williams share almost nothing in common, belonging to two different branches of conceptualism, despite Thomas Crow’s attempt to connect their work and persona in his essay Unwritten Histories of Conceptual Art: Against Visual Culture [1]. Ader’s death was not a suicide, but a mystery—he simply vanished. His body was never found, while D’Arcangelo’s was offered bare. Perhaps the correlation Williams references in this image, indeed mortuary, is not a flattening of these different trajectories, but an edifice of each artist’s continued post-mortem contributions to these two conceptual sects—the anarchistic and the sentimentally poetic. Because Williams is neither. The death of conceptualism is where Williams begins, where he must start, by virtue of his project. This image, while it cites a type of monumental dedication, is an emptying out of all conceptual tenets attached—a highly produced and replicated studio documentation of the archival image we signify with bouquet, so pictorially present and undeniable that it would actually pose an affront to the non-image-based artists it claims as their voucher. It exists as an image with no mirror and no source, a simulacrum of our twentieth-century index.

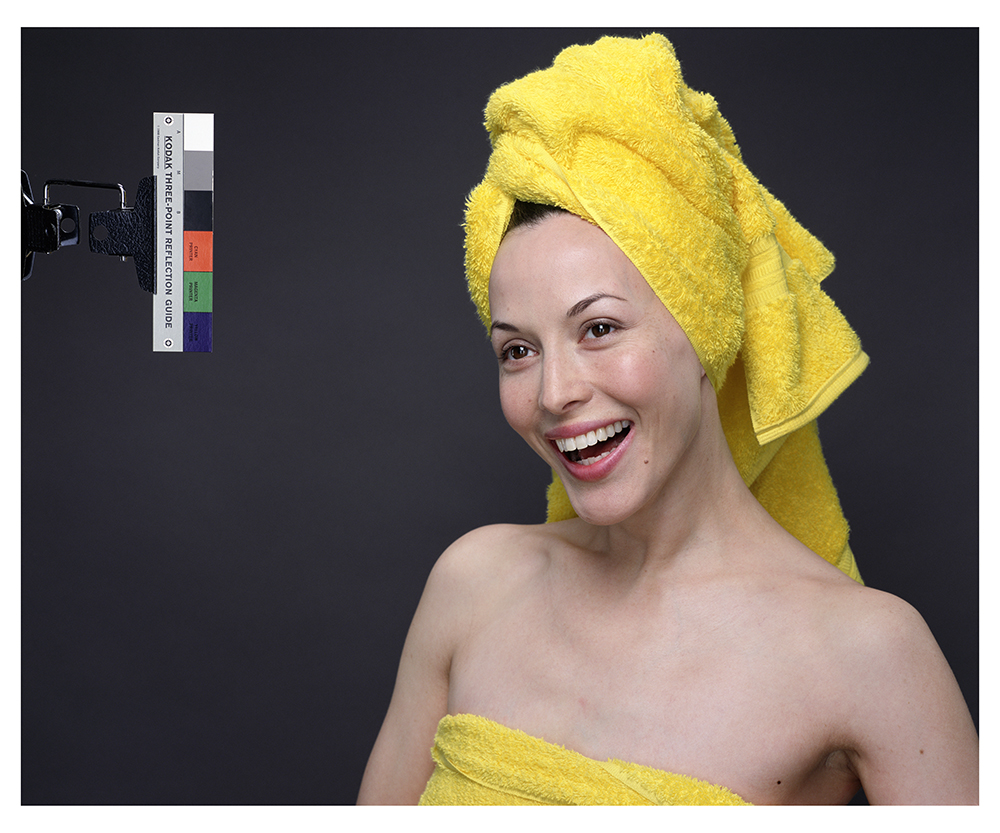

Christopher Williams, Kodak Three Point Reflection Guide, © 1968, Eastman Kodak Company, 1968, (Meiko laughing), Vancouver, B.C., April 6, 2005, 2005. Glenstone; © Christopher Williams. Courtesy of the artist; David Zwirner, New York/London; and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne.

However, to admit to this conceit would forfeit Williams’ argument. The insistence that this image, as well as any other, has been defeated by familiarity is one that Williams quietly proposes, so silently that it could be mistaken as the thing itself. A type of steganography, as David Hartt proposes, that encodes Williams’ agenda in such a way that no one, apart from the sender and intended recipient, suspects the existence of a hidden message. The affect of many of the images on view is that of tacit contempt, a hostility toward their more prominent allusion—the stranglehold of the commercial, capitalist, and neo-liberal influence on culture. As Marc Fischer suggests, since the fall of the Berlin Wall, the world waited for the absence of capitalist propaganda, of advertisements, of commercials—but this form of image prevailed, nothing appeared in its place. Nothing further exists to distinguish the lies that capitalism fostered in our image consciousness through the Cold War as capitalism no longer exists in opposition to another dominant regime of images. The illusion became the material, a dream conflation of the failure on the left. This aesthetic of consumer pleasure exists on the surface of every image in the exhibition. As with the bouquet, one of Williams’ most well known images, Kodak Three Point Reflection Guide, © 1968, Eastman Kodak Company, 1968, (Meiko laughing), Vancouver, B.C., April 6, 2005,transforms the unexpected into the reconstructed. As we pass image after image composing the exhibition, the elements that are carefully staged appear frivolous or unintended—as if the viewer possessed some innate privilege, eternally discovering a series of happenstance occurrences, perfectly timed in every sense.

Two nearly identical copies of this image hang in the architecture and design galleries on the upper level of the Modern Wing, surrounded by extensive selections from Williams’ ongoing series For Example: Dix-huit Leçons sur la société industrielle, started in 2004. The two images are placed so that you cannot view them side-by-side, though they are hung on parallel temporary walls. The images face outward from each other, forever facing different directions, infinitely opposed. The differences between the same young woman’s expression are barely perceptible, the comparison existing only in your memory. The image consists of the same four elements: a darkened backdrop, pale white exposed skin, bright yellow bath towels, and a chroma key guide for the product. The only persistent mystery is her expression, laughing in one, though perhaps more coyly smiling in the other—or was it stern? Regardless, the expression evades memory until you view the piece; you must be in front of it—otherwise it vanishes. Not because the image is uncertain or undecided—but because it is so pointed, and so impossibly sure of itself that to remember the image is to erase it.

Christopher Williams, Model: 1964 Renault Dauphine-Four, R-1095, Body Type & Seating: 4-dr-sedan–4 to 5 persons, Engine Type: 14/52 Weight: 1397 lbs. Price: $1495, 00 USD (original), ENGINE DATA: Base Four: inline, overhead-valve four-cylinder, Cast iron block and aluminum head. W/removable cylinder sleeves. Displacement : 51.5 cu. in. (845 oc.) Bore and Stroke: 2.23 × 3.14 in. (58 × 80 mm), Compression Ratio: 7.25:1 Brake Horsepower: 32 (SAE) at 4200 rpm. Torque: 50 lbs. at 2000 rpm. Three main bearings. Solid valve lifters. Single downdraft carburetor, CHASSIS DATA: Wheelbase 89 in. Overall length, 155 in. Height: 57 in. Width: 60 in. Front thread: 49 in. Rear thread: 48 in. Standard Tires: 5.50 × 15, TECHNICAL: Layout: rear engine, rear drive. Transmission: four speed manual Steering: rack and pinion. Suspension (front): independent coil springs. Suspension (back): independent with swing axles and coil springs. Brakes: front/rear disc. Body construction: steel unibody. PRODUCTION DATA: Sales 18,432 sold in U.S. in 1964 (all types), Manufacturer: Régie Nationale des Usines Renault, Billancourt, France, Distributor: Renault Inc., New York, NY., U.S.A., Serial number: R-10950059799, Engine Number: Type 670-05 # 191563, California License Plate number: UOU 087, Vehicle ID number: 0059799 (For R.R.V.), Los Angeles, California, January 15, 2000 (No.6), 2000. The Art Institute of Chicago, Emilie L. Wild Prize Fund, © Christopher Williams. Courtesy of the artist; David Zwirner, New York/London; and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne.

How does the texture of these images, so tied to a mid-century moment, fit within our post-modern lexicon? I’ll defer once more to David Hartt, who spoke so beautifully about Williams’ challenging and willfully problematizing relationship to the photograph; he suggested a definition of the 21st century as the “great sorting,” as if to say that the next hundred years are meant only to organize and make sense of the intensely dramatic changes that took part in the 20th century, modernism in particular. If it is any indication, each image within the exhibition appears more abnormally and perfectly iconic than the one preceding it. If Williams does not render the iconoclast strange, then he certainly positions it in a more questionable light—a primary venture of one artist into the unwavering ether of hidden messages, unearthed from a not so distant past.

[1] Crow, Thomas E. Modern Art in the Common Culture: Essays. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 1995. Print.